Chef Pierre Thiam remembers the enthusiastic words from his co-workers that pivoted him toward where he is now: "Why don't you add these dishes to the menu as specials? People would love it!"

Thiam wasn’t yet a restaurant owner, but he was rising fast from his first job busing tables in New York City. He had started cooking favorites from his native Senegal for "family meal"—the staff-only dinner served before customers arrived at the restaurant where he worked. It was a revelation to his co-workers. They'd tried just about everything New York had to offer but hadn't tasted the beautiful blend of flavors, ingredients, and cooking techniques that the ugliness of colonialism had carried to his native Senegal. There, on the northwest coast of Africa, influences from France, Vietnam, and Lebanon are folded into local culinary traditions going back millennia.

01 / 02

Thiam described a typical dish: "The tomato broth has so much flavor. Before cooking the rice in it, we cook a fish stuffed with a spicy parsley mixture. Once the fish is cooked, you scoop it out, and you add vegetables: eggplants, cassava, carrots, cabbage. Then there's fruitiness from tamarind, acidity from lime, chili, fermented conch that adds so much umami. It's a dish to die for."

The great response from co-workers—and the popularity of his dishes when they appeared as specials on the restaurant menu—validated a belief Thiam had when he arrived in New York. "When I first started in restaurants, NYC was called the food capital of the world, but Africa was the big absence," he said. "I saw this as an opportunity."

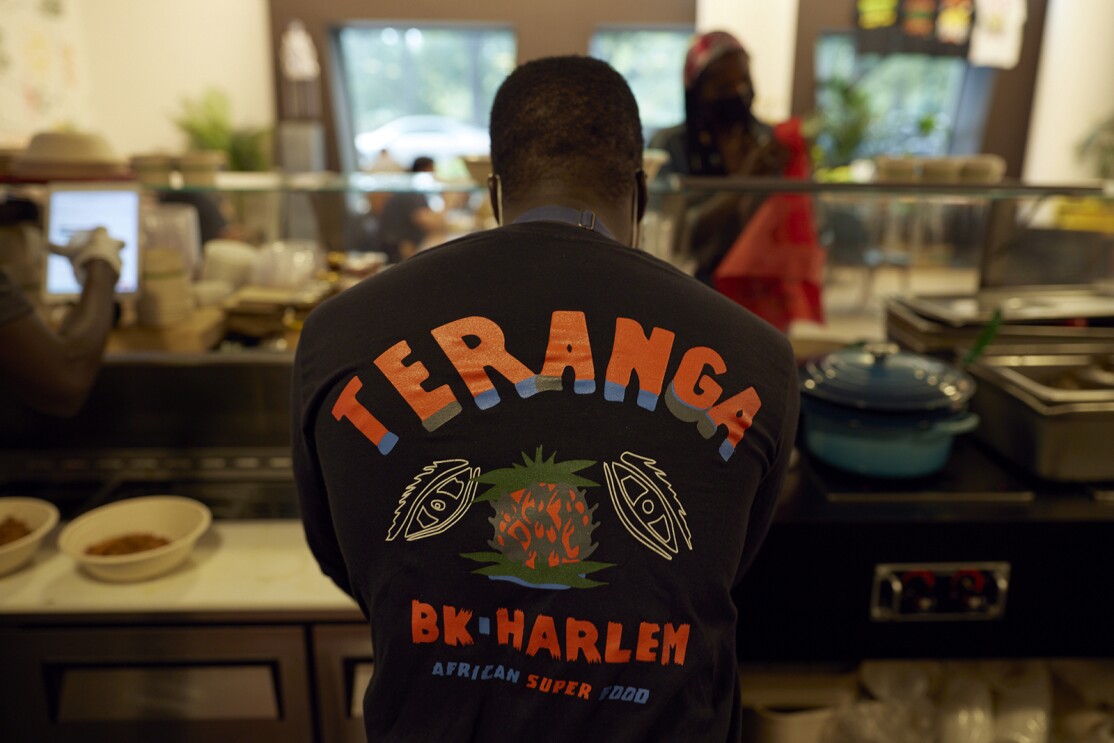

Maximizing the opportunity of that absence has since defined Thiam's career as a chef and an entrepreneur. He now runs restaurants where African flavors are the star attraction, not occasional specials.

01 / 04

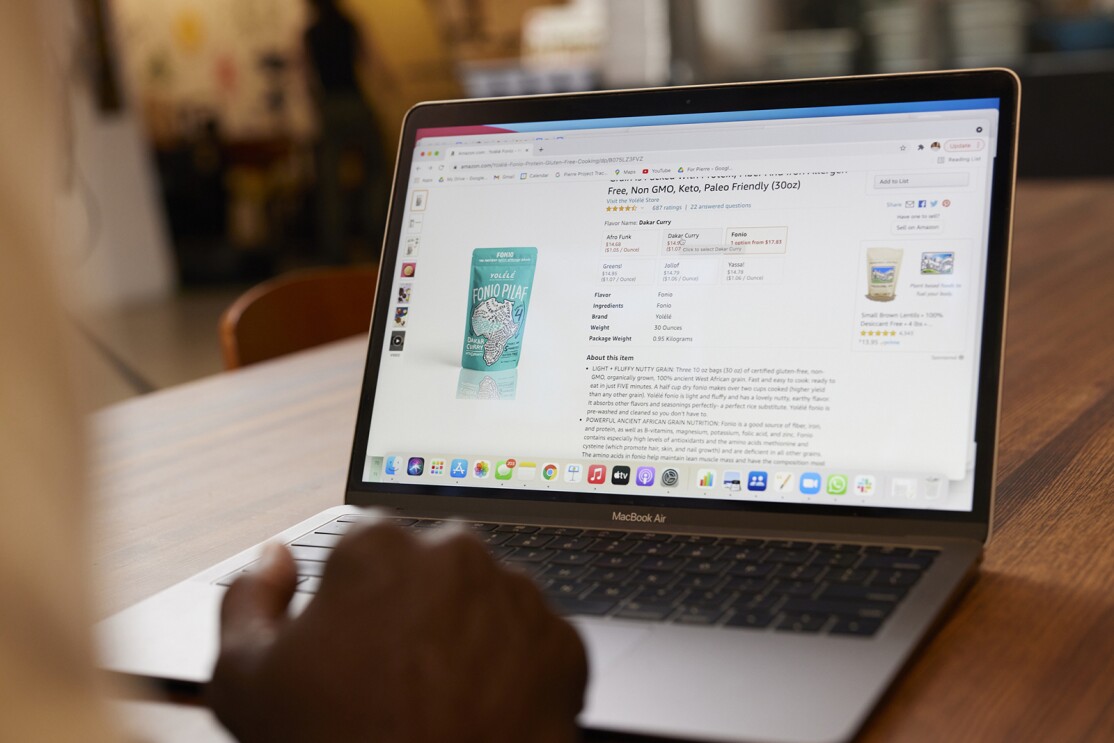

Thiam and his business partner, Philip Teverow, also created a food brand called Yolélé and started selling it on Amazon. They began with fonio, a grain that Thiam’s grandmother served to him when he was a boy. It was one of the ingredients he couldn't find in the U.S., and he believed it checked "so many boxes" that people around the world would embrace it.

"Fonio is the oldest cultivated grain in Africa," Thiam said. "It's very nutritious, and it cooks in five minutes. It has a nutty flavor, and it's versatile because it's neutral. It takes the flavor you add but doesn't contrast with it. Also, when you look at climate change, we have this food system that uses crops that demand so much water. Fonio is drought-resistant and has deep roots that slow the advance of the desert by restoring the topsoil."

"The great thing with Amazon is the user feedback," Thiam said. "It really tells us where our customers are and what they think about our products. That's something we use quite a lot as inspiration for our future products or how we even transform our products."

Along with its Amazon store, Yolélé is now on the shelves of thousands of retail stores across the U.S.

Thiam said what's most gratifying is to be able to see the impact for farmers back in the region of Senegal where fonio grows. "The population is mostly women because the men are gone for the most part," he said. "They migrated either to the big city or are trying to migrate to Europe because there's no opportunities, they have no jobs. Our core mission at Yolélé was to change that dynamic. By opening markets, you bring economic opportunities, you bring jobs."

01 / 02

"It started with a dream, and I'm seeing this happening now," Thiam added. "We used to be importers of food, and now people who are among the poorest people in the world can export this amazing grain and feed the world. I'm able to give back and, most importantly, create a model of development for other cultures, other crops in Africa. Fonio is really just the beginning. We're going to come with other crops, other ingredients that Africa has been storing in secret for way too long."