Concerned about rats potentially sneaking into one of California’s more delicate ecosystems, the environmental nonprofit The Nature Conservancy (TNC) recently rolled out a real-time remote camera system for biosecurity on Santa Cruz Island, a mostly unpopulated 96-square-mile atoll in the Channel Islands. The five-island chain lies off the Southern California coast, visible on a clear day from Santa Barbara and Ventura.

A map of Santa Cruz Island, part of a five-island chain off the Southern California coast.

A map of Santa Cruz Island, part of a five-island chain off the Southern California coast.Although islands represent only 5% of total land mass on our planet, more than 60% of extinctions have taken place on islands—an outcome driven in many places by invasive species like rats. Rats have historically been kept off Santa Cruz Island, and that has been by design. TNC staffers know that just one or two of these furry gnawers making their way off a visiting tourist, commercial, or naval vessel could threaten wildlife with disease and predatory behavior, setting back decades of conservation investment.

The key to preventing damage to the fragile island ecosystem is early warning, before visiting rats have the chance to settle in and wreak havoc on Santa Cruz, said Nathaniel Rindlaub, a software developer with TNC.

“Rats are prolific reproducers,” said Rindlaub. “Just one pair of rats can produce up to 15,000 descendants in a single year. So if a pregnant rat got on the island, we would need to know right away to mount a meaningful response.”

An animation of a rat detection in Ventura Harbor, just feet away from the ferries that provide daily service to the islands. Image by Nathaniel Rindlaub, TNC.

An animation of a rat detection in Ventura Harbor, just feet away from the ferries that provide daily service to the islands. Image by Nathaniel Rindlaub, TNC.While TNC has experience removing feral pigs, golden eagles, and other invasive species from the island, the size and rapid reproduction potential of rats didn’t lend itself to traditional monitoring techniques. Typically, the preservationists would borrow an approach from hunters where they mounted battery-powered, SD-card-laden camera “traps” on coastal trees to keep a digital eye out for unwanted arrivals.

TNC staffers figured they would give the standard camera trap approach a try, but a series of problems quickly presented themselves. For starters, Santa Cruz Island is huge. To be more precise, it is California’s largest island. Its expansive terrain is also treacherous in spots, making it difficult and time-consuming for the TNC team to place cameras in smart locations—and to maintain them.

What’s more, because traditional camera traps are motion triggered, the batteries quickly drained with every rustle of a leaf or blade of grass. Meanwhile, the SD cards filled up with frame after frame of data, much of it blank or dark imagery triggered by a gust of wind, before they could be retrieved. None of it was particularly helpful for The Nature Conservancy’s mission of ensuring rats are kept off the island.

Santa Cruz Island. Photo by Nathaniel Rindlaub, TNC.

Santa Cruz Island. Photo by Nathaniel Rindlaub, TNC.“Because they were spread so far afield, we could only really hike out to the cameras about once every three months for maintenance or to fetch data,” said Rindlaub. “This basically created a very long lag time in which rats, or some other species that weren’t supposed to be there, could find their way onto the island and begin reproducing rapidly.”

In other words, any response would likely be too little—and far too late.

Rindlaub added that during the three to 18 weeks that the cameras were out in the field collecting data, a lot went wrong between SD card malfunctions and battery issues. In fact, TNC was consistently losing 10% of its potential data. The solution they landed on was to invest in about 30 solar-powered camera traps (eliminating the drained battery issue) with radio-based, live-streaming capabilities.

A wireless camera on the North Ridge on Santa Cruz Island. Photo by Nathaniel Rindlaub, TNC.

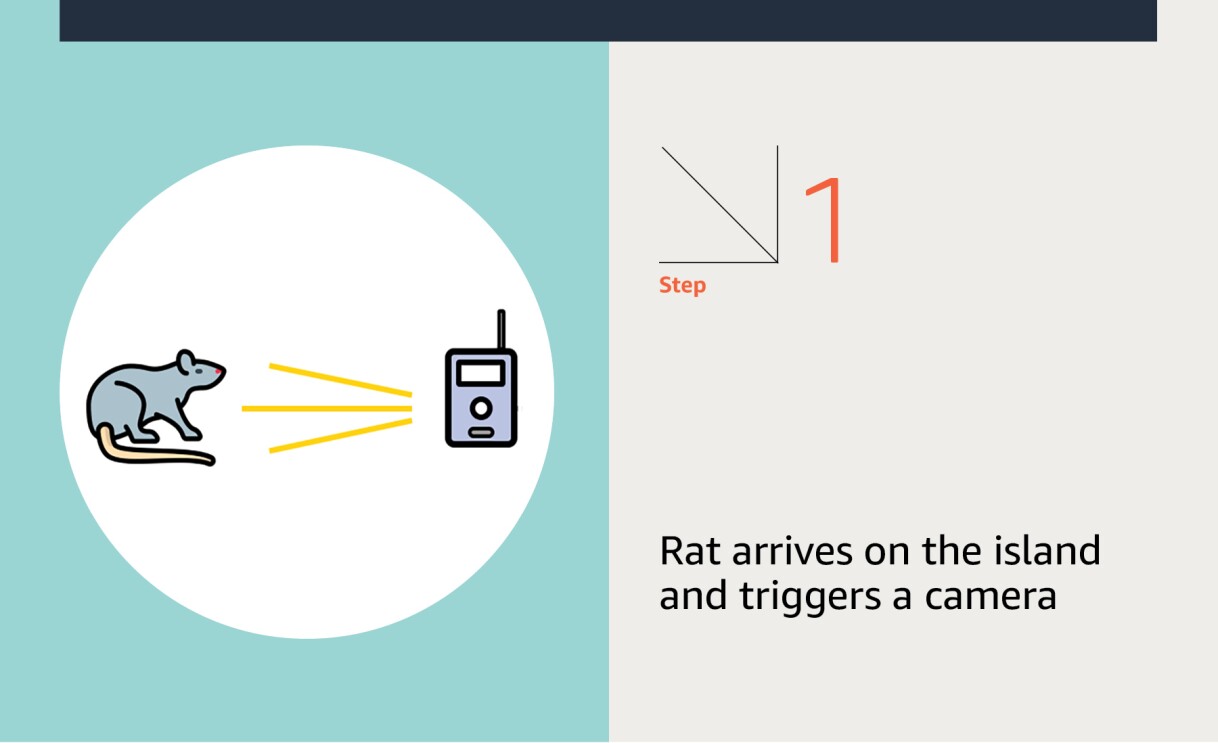

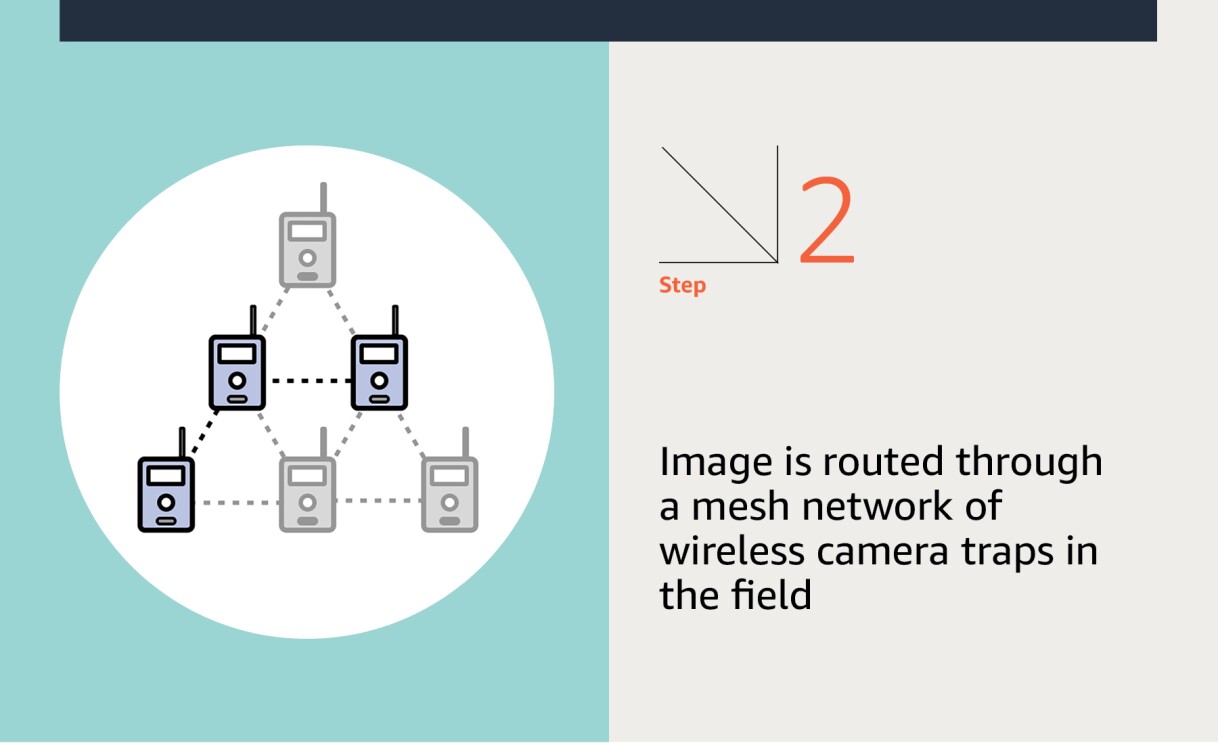

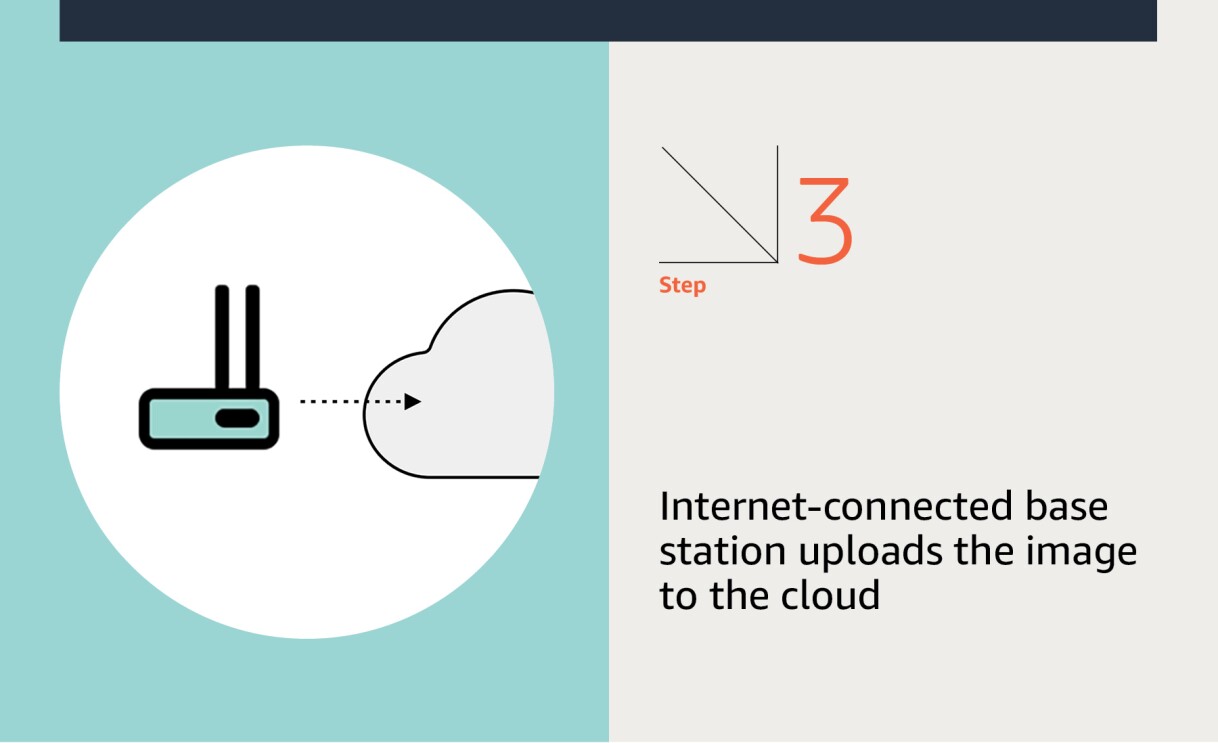

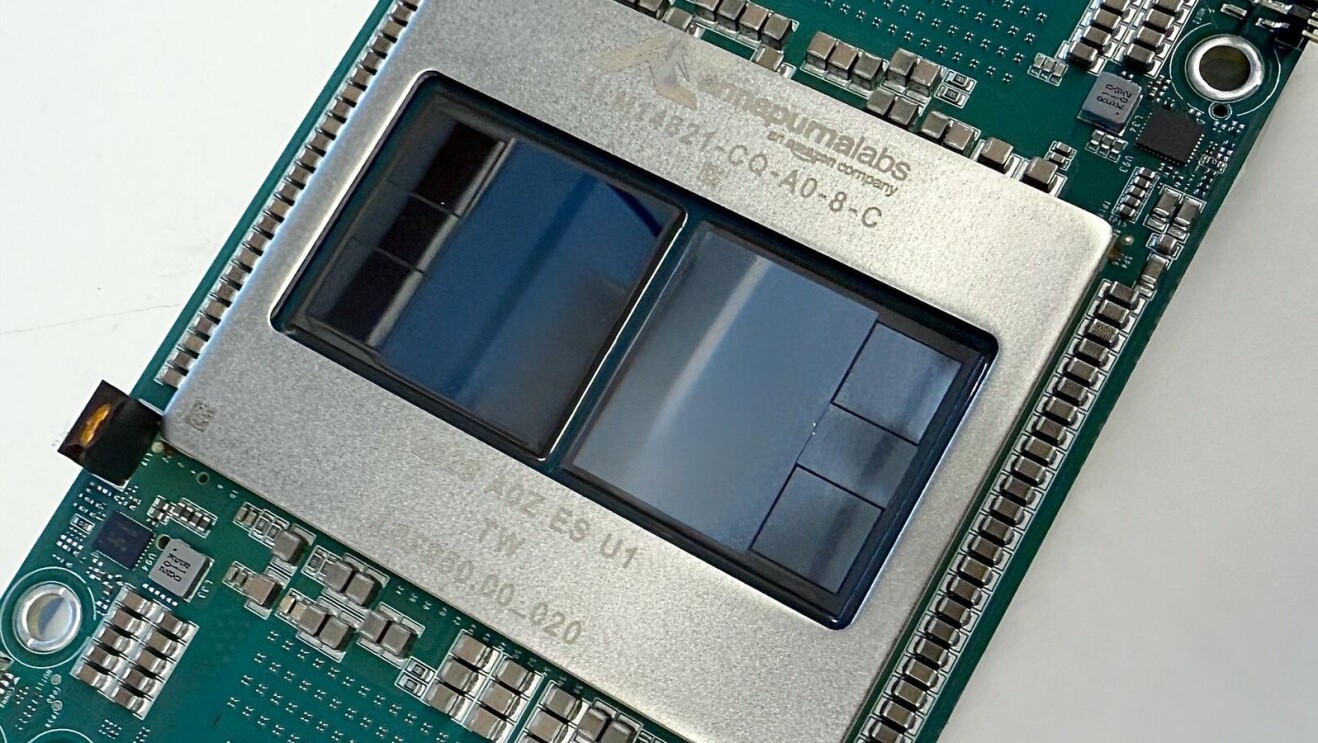

A wireless camera on the North Ridge on Santa Cruz Island. Photo by Nathaniel Rindlaub, TNC.Here’s how it works: Cameras and repeater nodes, linked together, form a wireless mesh network across often difficult-to-reach island terrain without Wi-Fi or cellular service. When a camera fires, its image is sent through the mesh network until reaching a Wi-Fi-connected base station. At that point, the data is pushed to Animl, an AWS-hosted camera trap data management platform, which Rindlaub built with support from the AWS Global Impact Computing team.

Animl follows a largely serverless, microservice-based architecture, and it uses a variety of AWS infrastructure, including Amazon Simple Storage Service (Amazon S3), AWS Lambda, Amazon API Gateway, Amazon Cognito, Amazon Simple Queue Service (Amazon SQS), Amazon Simple Email Service (Amazon SES), and Amazon SageMaker. Once the image is ingested into the system, it kicks off an automated image processing pipeline in which SageMaker-hosted machine learning models make predictions about what—if anything—is in the image (since many images, like smart doorbells, end up just being blanks).

01 / 05

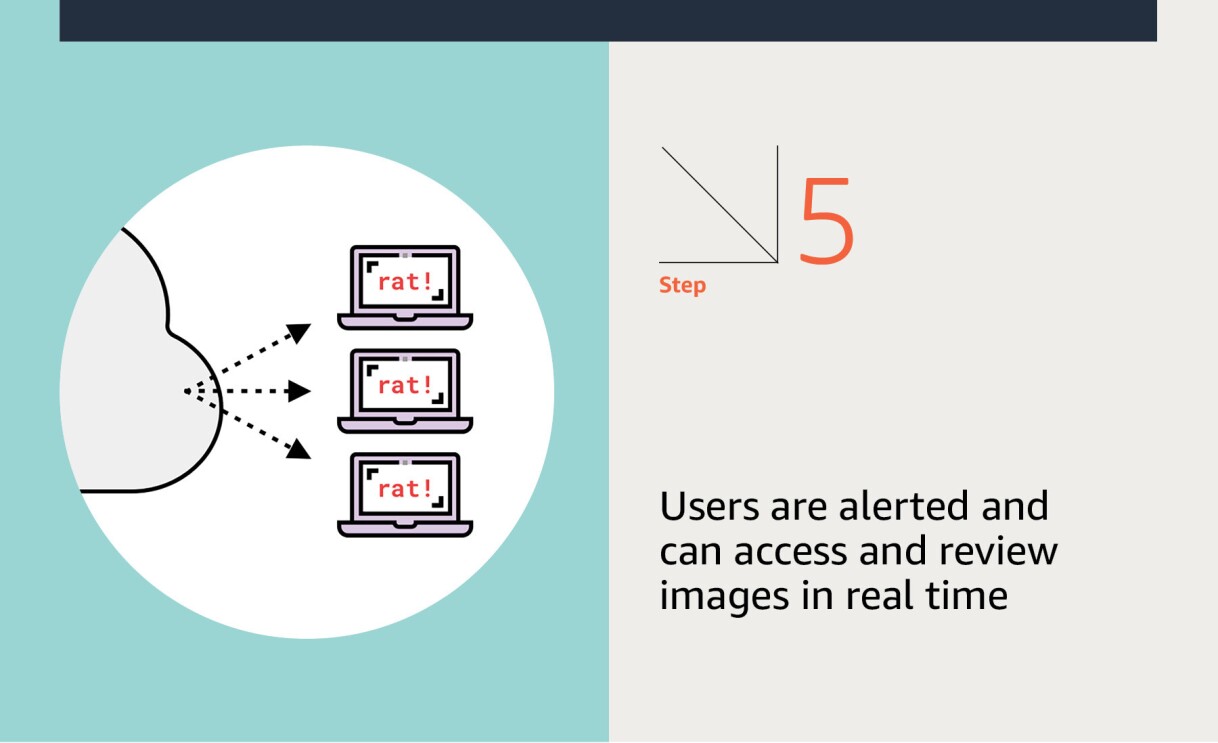

In short, all this automated technology comes together to logically scour through an unwieldy amount of visual data—far more than TNC staff and volunteers could possibly handle—looking for newly visiting rodents.

If anything is spotted, biologists receive an email or text alert to review and annotate the images. As the “humans-in-the-loop,” their job becomes double-checking the artificial intelligence (AI) conclusions about what it conveys it has seen, because the technology is far from foolproof and does occasionally miss things, Rindlaub said.

“The challenge from a computer vision perspective was that we knew we were going to see a lot of rodents,” he said. “But we needed to be able to also distinguish between the mice and the rats. Because one is supposed to be there, while the other is not.”

An island fox makes quick work of an island deer mouse on Santa Cruz Island. Image by Scott Meyler and Juli Matos, TNC.

An island fox makes quick work of an island deer mouse on Santa Cruz Island. Image by Scott Meyler and Juli Matos, TNC.“It’s great to see this innovative application of machine learning technology assisting TNC in their important fieldwork on Santa Cruz Island," said Marko Cemovic of the AWS Global Impact Computing team. "We’re really excited to see how this repeatable approach for biosecurity will be deployed elsewhere to protect habitats."

The Santa Cruz Island project could have sweeping implications for other environmental efforts. TNC has expanded its project hunting for nonnative species to nearby Santa Rosa Island and is planning deployments on Catalina Island, to the south, and Anacapa Island, to the east. It’s also eyeing possible projects in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, an island near Bermuda, and Palmyra Atoll.

Rindlaub acknowledges all of that will take time. Needed cellular or wireless infrastructure might not be ready. And the budget will have to be there as well, something nonprofits sometimes struggle to find.

“But there are certainly other islands facing their own invasive threats,” said Rindlaub, “and it would be really cool to extend this program to other species.”

Photo #1 of Santa Cruz Island was taken by Sue Pollock, TNC.

Trending news and stories