“We want people to be able to participate in space exploration, even if they don’t know anything about the sky,” said Arnaud Malvache, co-founder and chief technology officer of Unistellar, a startup and Amazon Web Services (AWS) customer that wants to open up the “sometimes secret-feeling world” of astronomy.

Unistellar, which has one foot in Marseille, France and the other in Silicon Valley, has created a series of easy-to-use digital telescopes that marry traditional astronomy with tech. Its lightweight, connected devices allow thousands of people with no prior knowledge of galaxies—or understanding of the equipment normally needed to observe them—to experience breathtaking views of the night skies, and to support scientific research by sharing their data via the AWS cloud.

Photo by OLIVIER PIRMAN

Photo by OLIVIER PIRMANUsing the Unistellar app as a remote control, even when offline, users can direct their telescope to specific points in the sky.

“You can click on what we call a recommended ‘object’ in the app, and the telescope will automatically focus on it,” said Malvache. “The app might, for example, suggest something that is ‘appearing soon,’ or ‘fading soon.’ It's actually the coolest feature from most users’ points of view. “In traditional telescopes, the sensor is your eye and the processor is your brain,” he added. “In our telescopes, the sensor is a camera and the processor is an embedded computer. The eye and the brain are amazing, but they’re not optimized for observing the sky at low light. We use a low-light sensor to provide up to 100 times more light through the eyepiece, to deliver incredibly clear images. We also remove light pollution, meaning you can pull your telescope out of your backpack in a downtown district and stargaze without having to go a remote place. Or hide in an attic.”

Taking astronomy out of the attic and making it accessible to people all over the world is exactly what Malvache and Unistellar co-founders Laurent Marfisi, Antonin Borot, and Franck Marchis have been on a mission to do ever since they launched their signature telescope, the eVscope, on Kickstarter in 2017.

Initially, they experienced suspicion from astronomers, many of whom didn’t think it was a “proper” telescope, but rather a digital camera that was somehow circumventing the traditional way of viewing the galaxy.

“A lot of people, including some of my colleagues, thought that I was wasting my time,” said Marchis, who, in addition to being Unistellar’s chief scientific officer, serves as senior planetary astronomer at the SETI Institute in California, a nonprofit dedicated to exploring the origins of life in the universe.

“Suddenly, I was giving up on this golden access to big telescopes to work on these tiny devices, which were, in their eyes, not capable of doing much,” he continued. “Now they’ve changed their minds. They all want an eVscope.”

Early skeptics aside, Unistellar’s initial popularity surprised even its founders. Expecting to move a few hundred units with their first Kickstarter outing, they sold almost 2,000.

“In 2021, we went from storing 5.7 million uploaded images to 27.7 million,” said Malvache, who credits AWS storage and compute services with Unistellar’s ability to grow at such rapid pace.

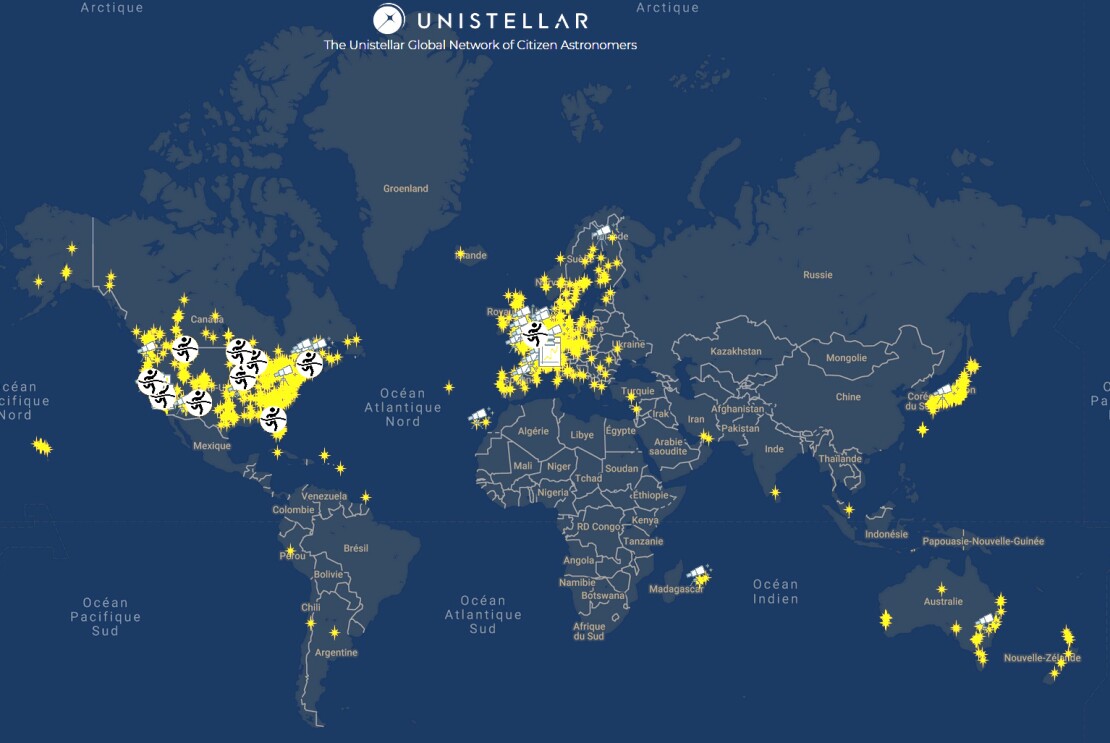

The company now has more than 7,000 customers, largely across North America, Europe, and Japan—part of what Marchis describes as the “biggest connected network of telescopes in the world.”

“We almost have a full cover range of Earth,” he said. “We’re continuously monitoring specific targets such as asteroids, comets, and exoplanets—planets orbiting stars outside of our solar system. If something happens in the sky right now, I can send a message to our network and someone will start observing it.”

The Unistellear Global Network of Citizen Astronomers

The Unistellear Global Network of Citizen Astronomers The network Marchis refers to is the Unistellar community of citizen astronomers, who use their eVscopes to record images and gather data on astronomical events, and share it on the cloud with research institutions like NASA and SETI.

“We store the data on AWS, then we analyze the quality,” said Malvache. “‘Was the user pointing the telescope in the right direction?’ ‘Were there any clouds?’ And so on. We do a first analysis of the scientific results on AWS as soon as we receive the data and we give the user a report as quickly as possible. Our users want fast feedback and it encourages them to participate again. The cloud allows us to do this. That's why AWS is really convenient for us.”

Last year, these citizen scientists were invited to take part in more than 800 campaigns organized by Unistellar, helping NASA and SETI to fill some of the gaps in their research.

“We have thousands of telescopes working at the same time, in different locations,” said Malvache. “It means we can see an event from different angles. So, for an asteroid, we can get a sense of its shape, because we’re not only observing it from one vantage point.”

In addition to supporting scientists, Unistellar is putting eVscopes in the hands of a new generation of astronomers. Both the Girl Scouts and U.S. community colleges have bought eVscopes—with the Girl Scouts now offering badges in astronomy, and several community colleges using eVscopes to integrate astronomy into the curriculum.

“Our users are already extremely diverse in terms of gender and nationalities,” said Marchis. “I’d say our greatest achievements so far have been making it easier for people to participate in science and observations, and growing the community of citizen astronomers in different countries. And we want to do more.”

Although the eVscope is more powerful and easier to use than most traditional telescopes, it’s not yet at a price point that makes it accessible to as many people as its creators would like. But as with the smartphone before it, Unistellar hopes to make the eVscope more affordable as it grows, and ultimately sell it in countries that have historically had limited access to stargazing equipment.

A recent partnership on lenses with camera company Nikon could be a “game changer” in this respect, according to Malvache.

“We have the goal of going to really high volumes in the consumer market,” he said. “Nikon has the experience to help us do that.”

“We will have our first eVscope customer in Kenya soon,” added Marchis. “My dream is that one day we will have our telescopes across sub-Saharan Africa. This new astronomy really is an astronomy for everybody.”

Trending news and stories