Growing up in Seattle in the early 1990s, Brad Jefferson, co-founder of Animoto—a platform designed to help anyone, anywhere, to create customized, professional videos online—remembers a distinct feeling of possibility in the air.

“We were surrounded by a lot of early adopters of technology,” he said. “There was an understanding that you could come up with an idea to do something cool for your family, your community, or your school, but then if you added software and the internet to it, you suddenly had the potential to make it available to the whole world.”

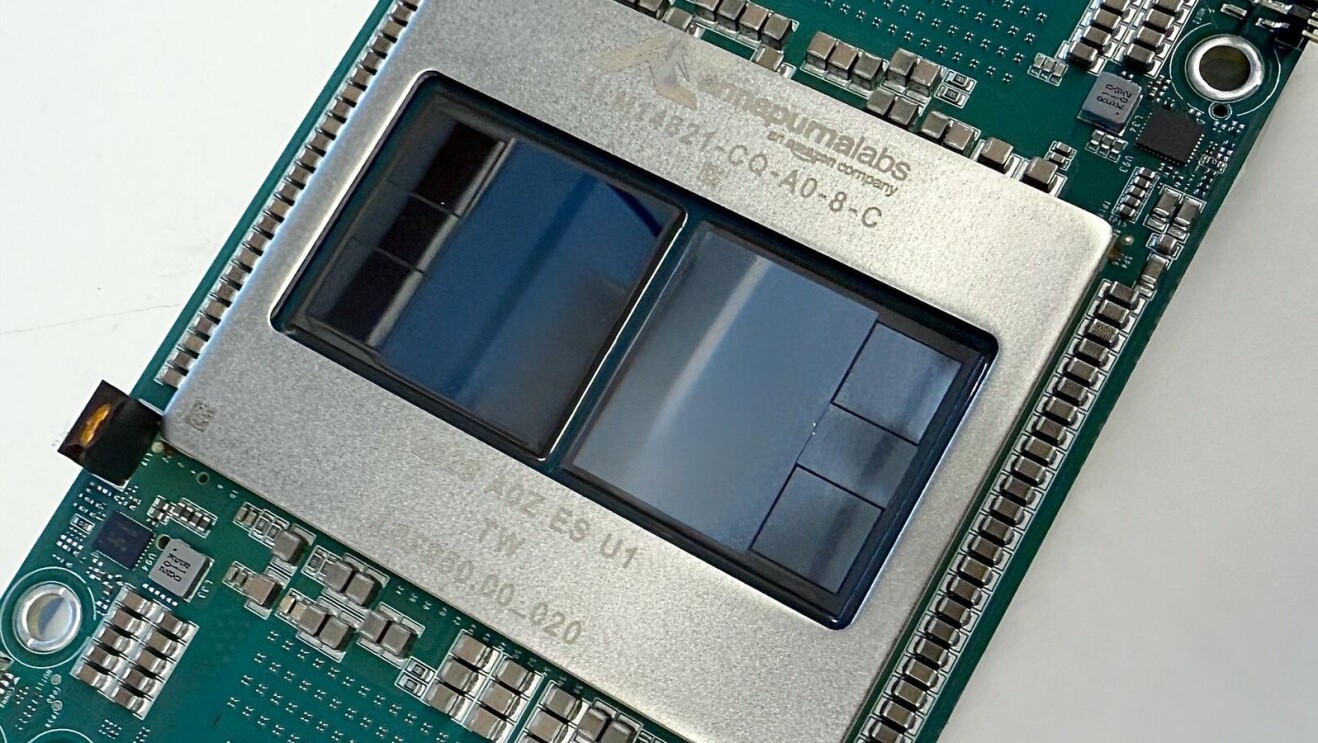

Fast forward to 2006. The idea Jefferson and his three co-founders wanted to make available to the world faced a common obstacle encountered by many startups trying to harness the potential of the internet in that era—computer processing power, or not enough of it.

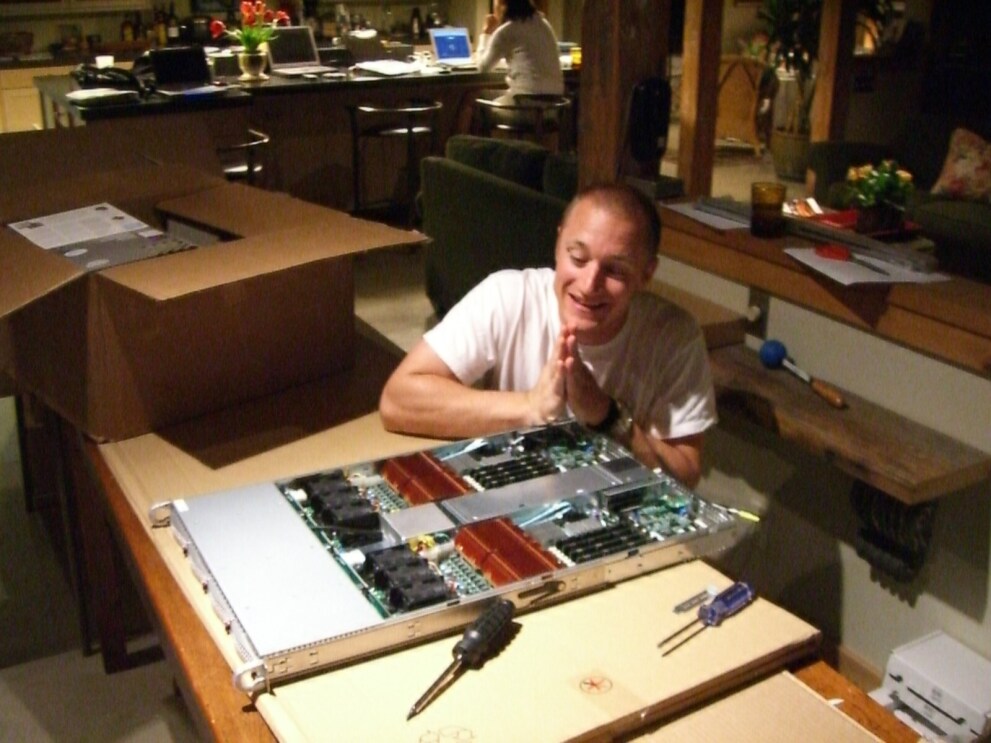

Brad Jefferson of Animoto built the company's own servers by hand back in 2007.

Brad Jefferson of Animoto built the company's own servers by hand back in 2007.“What we were proposing was far more technically complicated than we initially imagined,” said Jefferson. “We quickly realized that if we were successful and experienced the kind of spikes in usage we were expecting, our servers would immediately crash. But if we managed to find the tens of thousands of dollars required to buy more servers, and no customers came, we’d be in a huge amount of debt with nothing to show for it.”

It was hardly the kind of limitless possibility Jefferson and his co-founders had come to believe in.

In the logic tree of outcomes, all paths led to failure.

Animoto’s business model relied on its ability to render videos, and render them quickly—something the company had the computing capacity to do if the rate of demand remained steady, but not if lots of customers suddenly tried to use the service at once.

“Let’s say 1,000 people wanted to create a video on Animoto at the same time,” said Jefferson. “Our server would need to crank through these projects one by one. If each project took five minutes, that’s 5,000 minutes—almost three and a half days.”

“If you were the first person in line, you’d get your video back pretty quickly. If you were the last, you'd be waiting a very long time. What we really needed was an infinite amount of servers, available at the flick of a switch.”

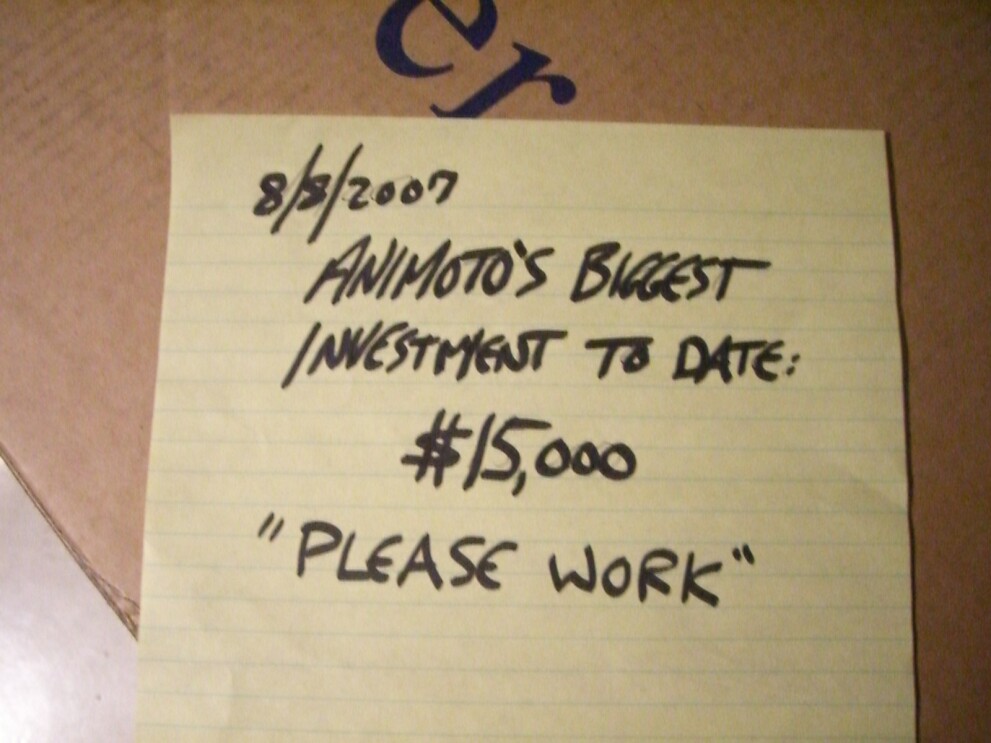

Animoto invested in their own servers but quickly realized they would not be able to scale to meet demand.

Animoto invested in their own servers but quickly realized they would not be able to scale to meet demand.The problem of how to prepare for the kind of wildly optimistic peak in demand, which could be a make-or-break moment for an aspiring business, was one that Amazon Web Services (AWS) recognized and was trying to solve. From AWS’s earliest days, its cloud computing services were designed to free entrepreneurs from investing upfront in hardware that may or may not meet their growing (or shrinking) needs.

AWS had already opened possibilities for anyone wanting to build a business with the launch of Amazon Simple Storage Service (Amazon S3), a groundbreaking service that allows people to store and retrieve any amount of data, from anywhere on the web.

Shortly after Amazon S3 became available, AWS took the next step and offered customers on-demand access to the kind of computing power previously only accessible to Fortune 500 companies.

This follow-up to Amazon S3 was Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2), which helps businesses instantly scale their computing capacity to handle spikes in popularity. It would prove the difference between success and catastrophic failure for Animoto and thousands of other companies like it. They just didn’t know it, yet.

“It seems like an obvious choice now, but back then, it definitely came with risk,” said Jefferson. “First, we didn’t even know if we could pull off the move to EC2, which meant delaying our public launch several months, so we could rebuild everything within AWS. Second, we wouldn’t know for sure if it really could help us scale during a massive surge in usage, until that massive surge came.”

The Animoto team would find out soon enough.

A year after moving to Amazon EC2, the company launched a Facebook app at the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival in Austin, Texas—a move that led to the huge uptick in demand Jefferson and his co-founders had dreamt about, but not yet seen.

“Over the course of four days, we went from around 25,000 to 250,000 users,” he said. “Thanks to EC2, we had the ability to perfectly match the number of servers required to render videos with the number of customers who wanted to create them.”

“Crucially, no one ever had to wait more than a few minutes to get their videos back. That was the moment where we just said, oh my gosh—those six months of delay where we rebuilt everything on EC2 were so worth it, because if we hadn’t done that, these people would never have received their videos. The success would have killed the company.”

Animoto wasn’t the only fledgling business betting its future on AWS. Back in 2007, Darrell Benatar, co-founder of UserTesting, today a leading provider of on-demand human insights, and his business partner Dave Garr, wanted to offer companies online usability testing for their websites. Until that point, it was an activity that was carried out almost exclusively in person.

“Everyone knew that user testing was valuable, but nobody was really doing it because it cost so much and it took too long,” said Benatar. “We wanted to let companies post a job online, select a panel of participants that represented their target audience, set them tasks for using their website, and then receive a video of the panelists performing those tasks within 20 minutes.”

“We knew one of our key value propositions was fast access—to the user panels, and the resulting videos. Already, we could see we were going to run into trouble because we would have such a backlog of processing.”

01 / 02

UserTesting relied on servers in a co-location, or ‘co-lo’—a facility where businesses can rent space for servers and other computing hardware. According to Benatar, moving to AWS was the only conceivable option for handling and processing the thousands of videos the company was already accumulating—not to mention putting an end to some unnecessary sleepless nights.

“Computers used to freeze up a lot more often back in those days,” he said. “I remember so many times when I had to drive out to the co-lo at 3 a.m. to restart the server or swap out a hard drive. Like many other startups, our servers were in a rack with another company’s, and often, the other company had unintentionally disconnected our power supply."

I’d be wandering around this huge, freezing warehouse in the dark thinking, ‘Is this what starting a company is all about?'

Fortunately, Benatar no longer has to get up in the middle of the night to switch on a server. UserTesting has come a long way since those days, with its customers now ranging from startups to some of the world’s largest companies.

“The launch of AWS was on a par with the invention of the internet in terms of reducing the obstacles for startups to get going,” he added. “We simply could not have built our business without it.”

This year is the 15th anniversary of AWS. Learn more about the history of the cloud.