Deep in a rainforest in northern Republic of Congo, 50 microphones—hidden inside small boxes—dangle discreetly from trees across a vast, remote landscape roughly the size of Los Angeles.

The person responsible for the devices is scientist Peter Wrege, director of the Elephant Listening Project at Cornell University in New York. His goal is to capture the calls of the elusive forest elephants he studies.

Aside from the unwanted attention of a few squirrels, the microphones have gone largely unnoticed since Wrege, his team, and the Wildlife Conservation Society set them up in 2017. The microphones are continuously recording, picking up an average of one to two elephant calls a week—and an epic chorus of other wildlife in the process.

Knowing the value of the audio data to his own field of study, Wrege has now made the recordings—all 1 million hours of them—available to researchers anywhere in the world through the Amazon Web Services (AWS) Open Data Sponsorship Program, which covers the cost of storage for datasets of high value to the scientific community.

The files have vast potential for conservation research, according to Wrege. More and more scientists are beginning to use the so-called soundscapes as a way of monitoring biodiversity, by comparing samples of sounds recorded in the same place over a sustained period of time.

Wrege estimates his team’s audio data over the past three years contains the sounds of hundreds, if not thousands of species of mammals, amphibians, insects, and birds—from gorillas and chimpanzees to tree frogs and parrots.

“There is so much information in these recordings. You could use them to study any number of different animals,” Wrege said. “We know, for example, that the African grey parrot is in serious decline, and we know we have captured its calls. If you study this species, there could be very valuable data in there on its movements and behavioral patterns.”

“One interesting thing we have learned so far is that the elephants are regularly in an area in the southwest of the region, which was used for logging in the past. They seem to like this, as do gorillas, because of the increased secondary growth of vegetation, which offers more food sources,” Wrege said.

“No one has ever been able to look at this sort of shifting use of an environment by an elephant population before,” he added. “The real take-home from our first set of analyses is that their use of the landscape is very complex. This is vitally important for thinking about conservation strategies and potential effects of climate change on elephant populations.”

The audio data has also been instrumental in enabling the efficient deployment of anti-poaching patrols. Wrege and his team analyze the frequency of gunshot sounds they pick up in the recordings and share the information with officials at Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, where the research is conducted.

Initially, the monitoring showed more illegal hunting activity deep in the park than expected. It also indicated that hunting hot spots regularly shifted locations. As a result, the park deployed an increased number of poaching patrols starting in early 2018. The data now shows the efforts have had an impact on reducing poaching.

“There are just so many potential applications for the recordings,” Wrege said. “We wanted to share them on AWS so we can make them available to as many researchers as possible with an interest in conservation and biodiversity.”

It’s a data set that’s still growing, as Wrege’s camouflaged team of ever-listening microphones continue to record the natural songs and goings-on in this richly diverse and remote part of the world. “As is the case with so much in research, the more we find out, the less we realize we understand,” he said. “We still know so little about forest elephants. I think there are an unlimited number of scientific questions you can run on these data.”

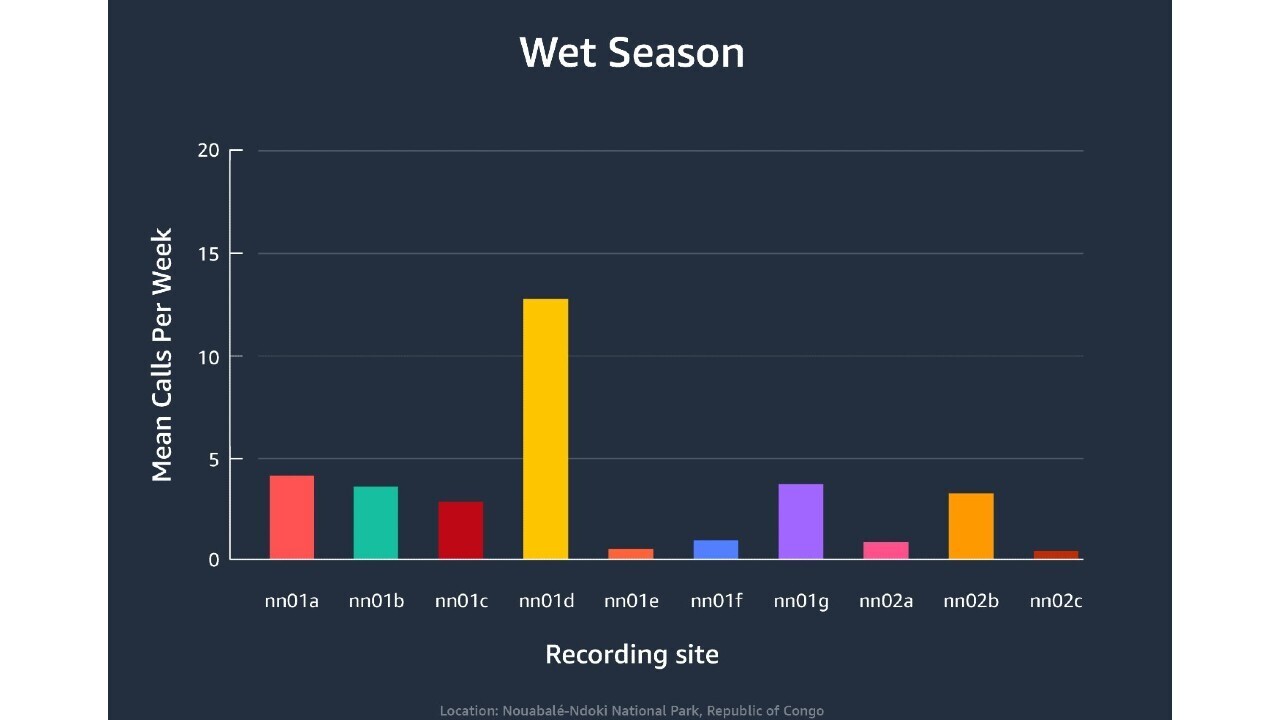

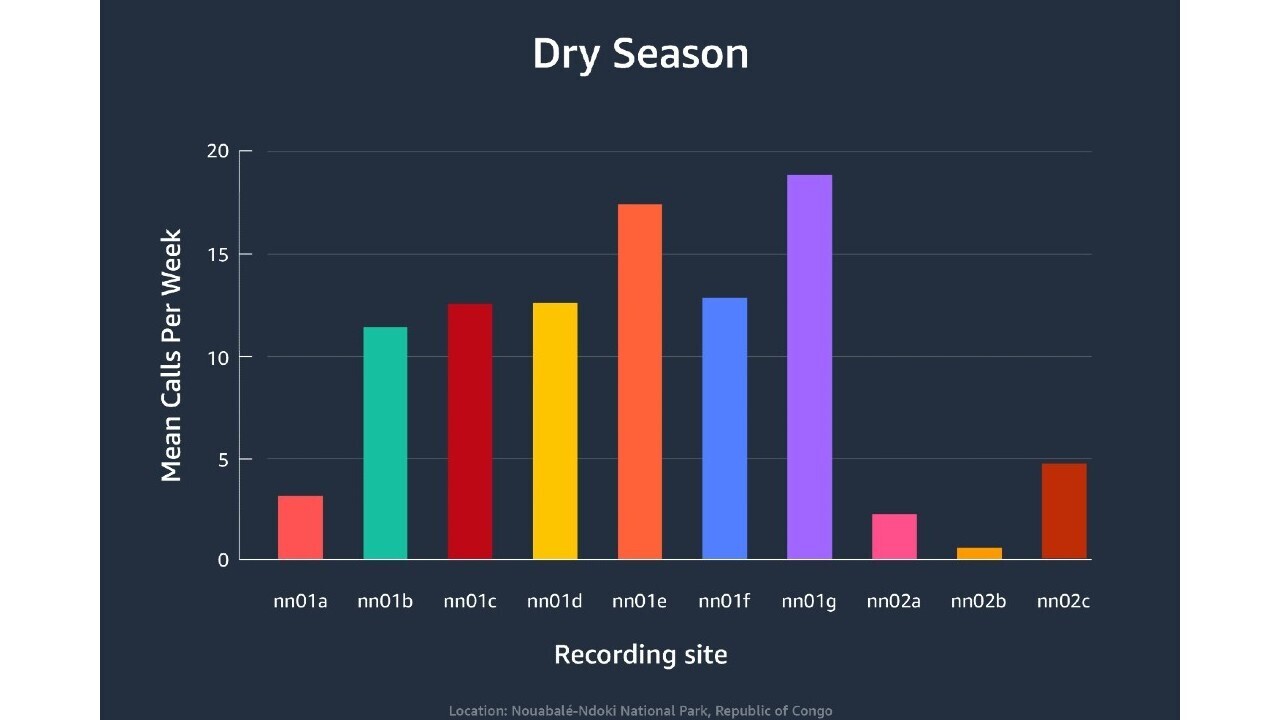

The charts below show the numbers of elephant calls recorded at 10 out of the 50 sites in the Elephant Listening Project, across a 1,250 km2 area of rainforest in Republic of Congo, between 2017-2018. Scientists are using this audio data to study elephant behavior and how they use the habit according to the season.

AWS Registry of Open Data

Sounds of Central African Landscapes is just one of many datasets made available in the cloud via the AWS Open Data Sponsorship Program, which covers the cost of storage for datasets of high value to the scientific community.

The program aims to democratize access to data by making it available for analysis on AWS, to develop new cloud-native techniques, formats, and tools that lower the cost of working with data, and to encourage the development of communities that benefit from access to shared datasets.

Trending news and stories