Even when it looks like just a wall of numbers, a dataset can paint a striking picture. Take, for example, your five-day weather forecast. That calculation boils down a mass of details – some of them from a U.S. radar network called NEXRAD – to allow you to see your upcoming weather. But when the NEXRAD archive of weather data recently became available on Amazon Web Services, a team of Cornell University researchers didn’t see just rain, sunshine, and wind patterns.

They saw something else entirely.

Accessing the data trove of weather radar allowed them to explore a poorly understood phenomenon happening across American night skies: bird migration. Their study tracked more than 4 billion birds moving south in the fall, gaining insights about where they went and which ones survived, and resulted from what they called “one of the largest datasets describing animal movement ever compiled.”

The Amazon Sustainability Data Initiative expands access to data that aims to drive sustainability innovation – hosting data archives such as NEXRAD on AWS. The initiative makes weather forecast models, satellite imagery, air quality measurements, and other public datasets more accessible in the cloud, and also provides computational tools for analysis.

This initiative came together over months of conversations between the teams in Amazon Sustainability and Amazon Web Services (AWS). Over time, the teams realized working together to improve access to datasets that Amazon needs to inform our sustainability goals could also empower the broader community of nonprofits, businesses, and academic researchers who can use this data. The Initiative was established to give anyone working on sustainability issues both knowledge of how to use the cloud and access to datasets that can be combined to offer new insights and drive new solutions.

The Cornell paper on bird migration is an "absolutely stunning study," said Ed Kearns, chief data officer for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the federal agency that runs NEXRAD. "This is something that, honestly, would not have been possible to do if these datasets were not available on the Amazon platform."

The power of the cloud

Amazon's sustainability team began working with AWS last year to begin warehousing the vast amounts of public data that describe our planet. While these datasets have always been freely available, researchers may not have the compute power necessary to take advantage of these resources through their own on-premise datacenters.

"If you're lucky and have a good internet connection and plenty of storage, you could download 1 terabyte in about a day and a half," said Jed Sundwall, open data global lead for AWS. The NEXRAD archive, for example, is 300 terabytes (a terabyte is 1,024 gigabytes). To put that into perspective, you could fit 500 hours’ worth of movies on one terabyte.

When data lives in the cloud – on remote, internet-connected servers – anyone can see it and analyze it without having to procure their own copy or worry about keeping it up to date. "This is really powerful," Sundwall said, "because it allows researchers to experiment much more quickly and at lower cost, which leads to more insights. It's not uncommon for us to hear from customers who say that they're now able to do things that would have been science fiction just a few years ago."

While the Amazon Sustainability Data Initiative started with the idea of aggregating resources in the cloud, it quickly turned into something more.

"Almost immediately, we found we were barely scratching the surface of the value we could provide," said Dara O'Rourke, senior principal scientist with Amazon's sustainability team and an associate professor of environmental and labor policy at the University of California, Berkeley.

In conversations with researchers, it became clear they needed not just access to the data itself but to technical expertise and computational tools, both of which Amazon has been able to provide. NASA, for example, recently used machine learning techniques on AWS to estimate hurricane wind speeds six times faster than their previous approach.

"Very few climate researchers would have any exposure to the most recent, cutting-edge machine learning and artificial intelligence tools, but they're potentially incredibly valuable to them," O'Rourke said. "So we're trying to get this data in this place where it's much easier to access and give these researchers a set of tools they've never had before."

Focusing the eyes in the sky

Together, the access and computational tools that AWS provides are driving sustainability projects led by groups that run the gamut from university researchers to local governments, federal agencies to private startups. Satellite imagery for five countries in Africa, for example, has been compiled in the Africa Regional Data Cube, a global partnership aimed at problems related to land use, water, and urbanization.

In Ghana, illegal miners raid patches of land over the course of a month, clearing trees and leaving behind puddles of contaminated water. "It's an environmental disaster," said Brian Killough, who is helping lead the data cube work through NASA.

Authorities in Ghana can only monitor so much ground with helicopters and planes. But "with satellite image every two to three days and a few fancy algorithms to go with it, you can find changes in an instant," Killough said. Available through AWS, the data cube—so named because it stacks layers of satellite data over time for a given location—is also helping to inform farming and urban planning. Killough said he hopes to scale the effort to other parts of Africa and the world.

AWS has also provided $1.5 million in cloud credits to the Group on Earth Observations (GEO), an intergovernmental organization, so that government agencies and research groups in developing countries can use big data to inform decisions for sustainable development. The grant was just announced in late November and will fund a broad range of projects, but Steven Ramage, GEO's head of external relations, said multiple requests have already come in related to disaster risk reduction tools and services.

"We want to help people help themselves," Ramage said, "and in doing so, enable us all to tackle some of the biggest challenges we have ever faced as humans."

Global reach, local impacts

While some of this work is clearly big-picture, it can just as easily come down to a single city block. In Virginia, flood-prone towns are using sensors to monitor water levels and upload them to the cloud as part of the StormSense project. Local residents can ask Alexa about water levels in specific places or subscribe to an app with alerts on dangerous flooding.

The data is also being used to predict where floods might occur and could eventually power signs that tell drivers to turn around when a roadway floods, said Sridhar Katragadda, data officer for the City of Virginia Beach, which is participating in the project.

StormSense is collecting data from coastal cities such as Virginia Beach, Newport News, and Hampton Roads. Katragadda points out that each locality may have its own system for capturing and presenting water levels, and those need to be reconciled in order for the project to grow.

"The only way you can scale this well is by being in the cloud," he said. "Different cities can use different sensors, but we can aggregate the data in one place."

01 / 02

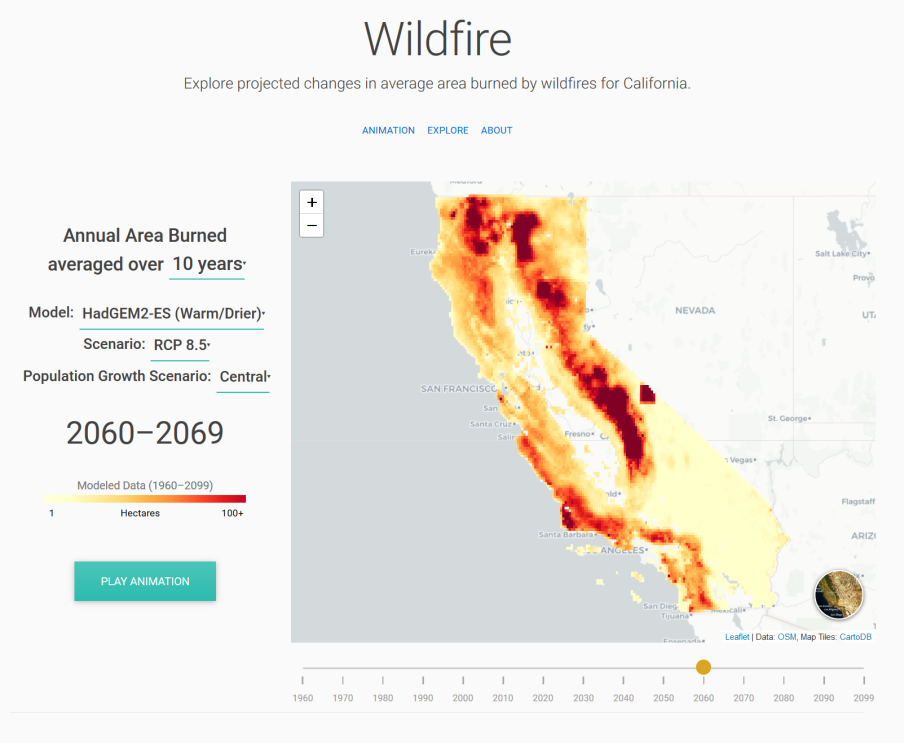

In California, the Cal-Adapt initiative is using AWS to open up climate data from the state's research community – details about sea level rise, wildfire incidence, snowpack levels, and other indicators.

"The next generation of global climate models are at higher spatial and temporal resolution than previous ones, and the model output includes more variables than ever before," said Nancy Thomas, Cal-Adapt's executive director.

Thomas said the group is using AWS Lambda to increase the computing power researchers can apply to daily climate parameters, such as the number of extreme heat days, in an interactive mapping format that can highlight climate anomalies over space and time.

"Open data access is critical to making complex climate research understandable, accessible, and actionable," she said.

Sometimes measurements are esoteric, and their immediate application isn't obvious, but after discussions with our experts, people go, 'Aha! This is how these data could be used.' That's really exciting for us.

Ed Kearns, chief data officer for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Building a data community

For NOAA, hosting NEXRAD data and other resources in the cloud has reduced the strain on its own servers.

"What's really nice about what Amazon is doing is they're providing these NOAA data with no discernible limits on how much data someone can consume," said NOAA's Kearns.

He adds that the ongoing dialogue between Amazon and NOAA experts helps shape what gets staged from the agency. Amazon conveys which datasets are interesting to its customers, and NOAA helps explain the datasets and how they can be used.

"Sometimes measurements are esoteric, and their immediate application isn't obvious," he said, "but after discussions with our experts, people go, 'Aha! This is how these datasets could be used.' That's really exciting for us."

As the Amazon Sustainability Data Initiative grows, it creates a flywheel effect: more data brings in more users, which in turn brings more data and more users. Many of those users are citizen scientists, entrepreneurs, or researchers like the ones from Cornell, coming up with entirely unexpected and creative insights from data that has long been too difficult to reach.

"When we worked with NOAA to open up access to their weather radar data, we never had thought it would be used as a dataset to describe animal movement," Sundwall said of the bird study.

"If you can get data into the hands of more people with different perspectives, different priorities, and different approaches, you're going to get much more out of it."

Trending news and stories