Churning up a muddy hill, the dark grey Jeep pickup truck appears to be just another very capably modified off-road rig. Lifted suspension, beefy wheels, and an array of extra bright lights on the cab. Not an uncommon sight in this wooded stretch of northern Virginia, which bumps up against the Appalachian mountain range. Then, the gate drops on the back of the truck, and things look decidedly more exotic.

The reflective orange badges on the truck’s sides are a clue to what’s inside and its purpose. They read, “AWS Disaster Response.” This truck, in true Amazon Web Services (AWS) fashion, is a cloud technology lab on wheels—a rolling platform designed to build and test cloud-based tools that can help first responders, humanitarian agencies, and victims during natural disasters.

With the Atlantic hurricane season starting June 1 and fire season on the West Coast imminent, the AWS Disaster Response team is getting ready with its field testing exercise program. The program is a new way for the AWS Disaster Response team to innovate around disasters. The goal is to bring together a handful of partner agencies and customers four to six times a year for three days of building and testing, to invent and refine new cloud-powered tools to help in disasters. The team is testing and innovating in areas such as edge processing and the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning for common disaster response use cases.

“Everything has to work flawlessly in a disaster scenario,” said Matt Johannessen, who heads up the AWS Disaster Response team. “In a disaster, there’s no room for error, and it’s no time to experiment. That’s why we are doing our experimentation and invention here—before disaster strikes.”

“Here” is nearly 1,000 acres of rugged territory including dense forest and uneven terrain. Much of this is used as a Boy Scouts of America camp in the summers—with a few rustic cabins providing shelter for the AWS team to store equipment and stay overnight during the exercises, with little or no reliable cell service or Wi-Fi. While it isn’t being torn apart by winds or under threat of fire, this slice of wilderness offers realistic conditions for the team to pressure test their equipment and procedures. “Networking in the dirt,” as some on the team call it.

Johannessen pulls the handle of a heavy rack attached to the bed of the truck. Out slide what look like two oversized carry-on suitcases. They are AWS Snowball devices, powerful and portable cloud computing devices designed for rugged deployments in the harshest physical environments. Johannessen connects them to a battery array in the bed of the truck.

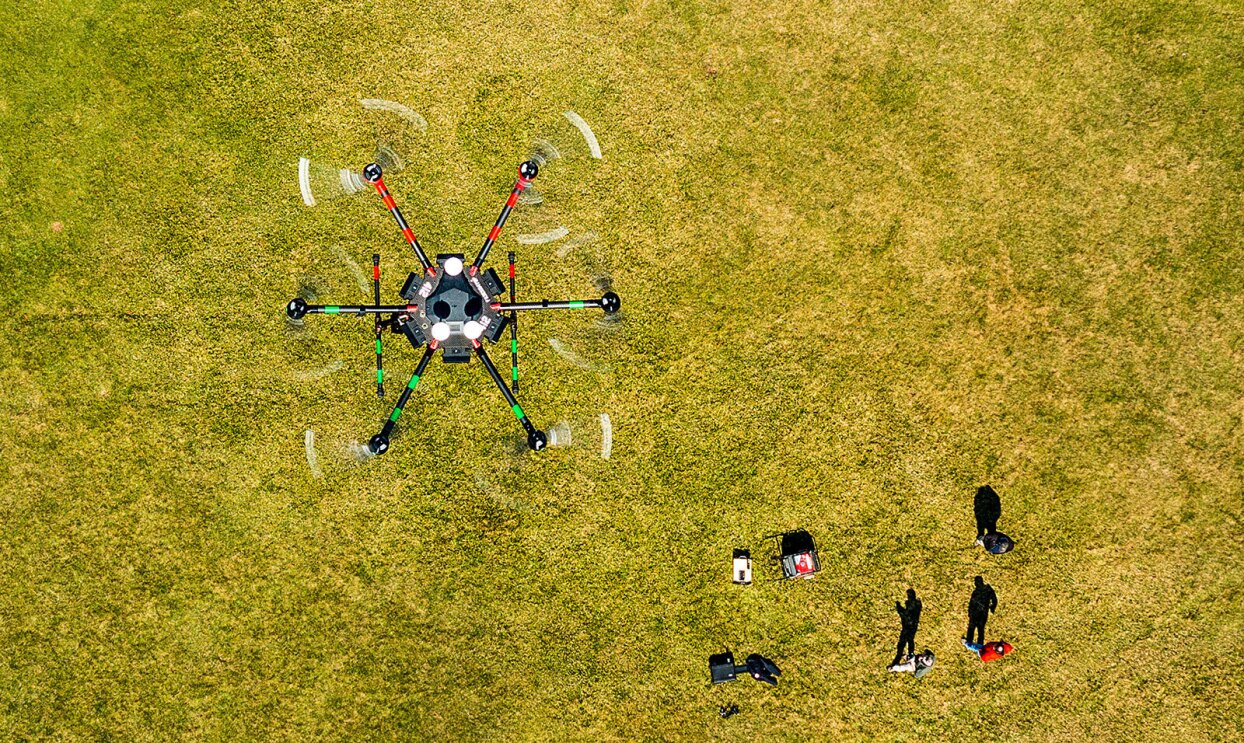

While those are booting, another member of the AWS Disaster Response team twists another handle connected to a steel panel on the left side of the truck, revealing two, 30-inch computer monitors. To the right of the Jeep in a small clearing, a mast antenna is pulled from cases, assembled, and cranked by hand 20 feet into the sky. A drone lifts off.

The screens come to life. One shows a live video feed from the drone’s camera, and the other has a detailed map of the hills and woods surrounding the vehicle. The map is scattered with bright green, slow-moving dots. The dots show the location of various AWS Disaster Response personnel across the 1,000 acres. This tracking simulates what responders refer to as “situational awareness,” which is a real-time picture of people or things that are deployed during a disaster. The map itself on which the dots are mapped was created earlier in the day by Kristi Rhoades, the operations lead on the AWS Disaster Response team, and several other team members who piloted a drone in a search-and-locate path across the entire property.

Detailed maps aren’t guaranteed in some locales, and up-to-date maps both during and after a disaster are key to search-and-rescue operations. These maps can assist in making decisions about where help is needed most and where it’s safest to relocate people, supplies, and temporary housing.

All this experimentation and invention helps us build better tools that can support decisions at every juncture in the disaster cycle.

Matthew Cua

Expert drone pilot and head of innovation at AWS Partner organization, Help.NGO

The drone mapping exercise was part of a drone pilot certification class led by Matthew Cua, an expert drone pilot and the head of innovation at AWS Partner organization Help.NGO. This exercise pulled double duty—as a training exercise for AWS Disaster Response members and volunteers, and as a practical way to map the area to support additional disaster response activities taking place over the field training exercise.

Cua, with a drone in hand, and Rhoades enter the lodge that is serving as the team’s base of operations and examine the maps they’ve generated in just a few hours.

Help.NGO began as Global Disaster Immediate Response Team. When there’s a disaster, they are often the first boots on the ground using the tools that have been developed in collaboration with the AWS team to establish communications and gather the data that can very quickly inform response and recovery. Help.NGO has evolved from an organization focused on meeting immediate needs to one that also works with organizations and institutions to prepare for emergencies before, during, and after their occurrence.

Cua discovered drones as a tool for mapping in his work as an environmental scientist focused on climate change disasters in the Philippines. Drones offer a fast way to collect high-resolution imagery and data. “But you have to process all that drone data,” Cua said. “That becomes incredibly difficult in the field due to limited or no connectivity. With devices like AWS Snowcone and Snowball Edge, we can process data immediately on-site, store terabytes of data, and deliver it rapidly to key decision makers on the ground in a useful form. When we get to a place where we can upload the data, we can do the complex data processing in the cloud, and deliver it back in a useful form on the ground very quickly.”

Access to processed data, connecting maps to accurate on-the-ground data about population and infrastructure, for example, is vital in every phase of a disaster, Cua said. Speed combined with accuracy is key. Before easy access to the cloud, somebody on Cua’s team or a partner organization would go out and draw a map, and then somebody would analyze the map and write a report with their findings and recommendations.

The data that comes back to Cua and the disaster response team in the field in potentially minutes—instead of hours, weeks, or months—is something people can use to make more informed decisions immediately following a disaster, with a view towards rebuilding sustainably. “That is what all this experimentation and invention is about,” Cua said. “Building better tools that can support decisions at every juncture in the disaster cycle from immediate response to recovery and resiliency.”

Disasters happen anywhere, and you have to go there to help.

Matt Johannessen

Head of the AWS Disaster Response Team

Back at the truck, Johannessen, Rhoades, and the rest of the team are debriefing on the day—what worked, what needs more work. Everyone agrees that the notion of a rugged, rolling cloud mobile has a lot of potential. In its essence, it’s a four-wheel-drive machine that can collect data and analyze it using the power of the cloud, fast, from anywhere.

“Having a reliable workload that runs in the back of a vehicle that you can extend to multiple individuals, and you know how it works, and you know how to get it from point A to point B is much different than building a solution in a controlled lab environment,” Johannessen said. “That's where this field exercise and this vehicle comes in. It’s a platform for our partners and customers who go into the field to build from and build on. Because the simple fact is that disasters happen anywhere, and you have to go there to help."